The Greferendum

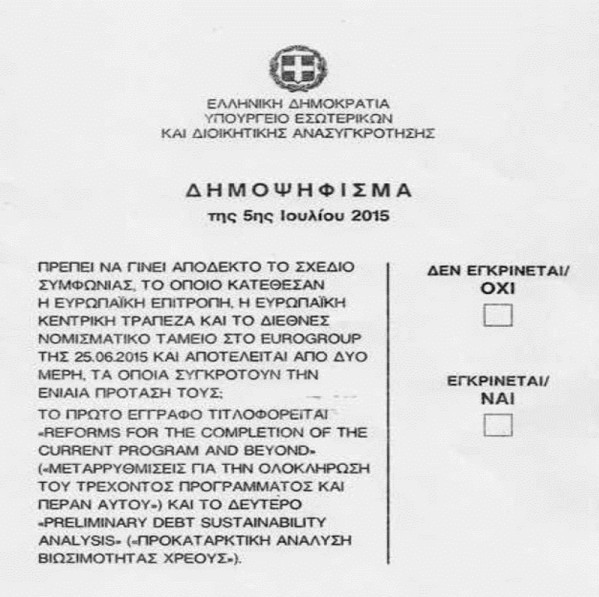

We’ll know more early next week when the result of this weekend’s Greferendum is known (assuming that is, that the referendum is carried through successfully; nothing is certain). Actually, the wording of the referendum is a little, erm, tame…

‘Should the plan of the agreement be accepted, which was submitted by the European Commission, the European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund, in the Eurogroup of 25.6.2015, and comprises two parts which constitute their unified proposal? The first document is entitled Reforms For The Completion Of The Current Program And Beyond and the second Preliminary Debt Sustainability Analysis’.

I had expected a more direct question about euro membership. I don’t doubt that that particular question will be addressed soon but, for now, the choice is simply ‘yes’ the deal that has been offered by the troika should be accepted or ‘no’ it should not be accepted.

If a ‘yes’ vote is forthcoming I see three possibilities…

- A fourth election in four years is set in motion. The current government is campaigning for a ‘no’, so a ‘yes’ vote probably undermines their legitimacy

- the current government leads new negotiations and, with further concessions, secures an interim agreement as a stepping stone to the next bailout proper

- the current government leads new negotiations which fail to secure an agreement; sparking another referendum (addressing euro membership much more directly) or, perhaps more likely, another general election

If, on the other hand, a ‘no’ vote wins I see two possibilities…

- The current government leads new negotiations and, with no further concessions, secures an interim agreement as a stepping stone to the next bailout proper

- The current government leads new negotiations which fail to secure an agreement; sparking another referendum (addressing euro membership much more directly) or, perhaps more likely, another general election.

Ultimately there’s the possibility of a Grexit either way. Clearly though, a Grexit is likely to happen much more quickly if the ‘no’ vote wins. For what it’s worth, I still think a voluntary Grexit is unlikely until the issue of euro-membership is directly addressed with the electorate. An involuntary Grexit – an expulsion from the euro-group – is the more likely scenario.

Super Mario (Draghi)

I’m not dismissive of the ‘contagion’ hypothesis. There is a real risk that discontent spreads from Greece to Portugal, Spain and Italy. And, if a crisis in the Greek mould makes it as far as Spain, it would almost certainly spell disaster. But before that happens I think we will see the European Central Bank (ECB) flex its muscles.

Remember, in July 2012, when Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, said ‘within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro… [and] believe me, it will be enough’. His statement had an incredible effect on bond yields in the euro-zone. Indeed, that statement alone was enough to limit the euro crisis and it prepared the ground for the nascent recovery we are seeing today.

Back then, the ECB was a central bank heavily constrained by an uncertain mandate. Now, senior court rulings on the legality of some of the ECB’s proposed measures (which had been subject to heavy legal scrutiny in the last three years or so) have defined and broadened the ECB’s mandate. In short, the ECB has considerably more power today than it did in 2012.

I am convinced that the ECB will indeed preserve the euro. I’m certainly not betting against it.

Implications for the stock market

Just to be clear, I’m still in accord with JP Morgan’s Stephanie Flanders on this one…

‘The key takeaway for investors is that the Greek crisis does not pose an existential threat to either the euro system or to Europe’s financial system. Ultimately we do not believe that Greece alone will be enough to put the European recovery into reverse, or that it will prevent a gradual improvement in European corporate earnings. But there is still plenty of scope for nasty surprises and renewed volatility if the Greek situation continues to deteriorate.’ (Source: JPM Market Insights, 19 June 2015).

And at the risk of repeating myself…

Back in 2011, when the euro crisis was at its peak, a Greek default would have been a catastrophe for the euro-zone. It would have spelt disaster for Europe’s banking system and various stock markets around the world would have plummeted. The same is probably not true today; a Greek default would not be a disaster either for the EU, the Eurozone or the stock market (in the long-run at least).

Of course, there is a great deal of complacency. Far too many managers and commentators are dismissive of a potential default; its eventuality would come as a shock to some and the stock market would react sharply while that complacency is washed away.

But does a Greek exit fundamentally alter the long-term potential for listed companies on the continent? How would such a happenstance irreversibly damage the likes of Daimler, Siemens, Louis Vuitton, Total, Airbus, Unilever or Heineken?

In conclusion

Investors should hold risky assets only in the proportions that they are willing and able to hold for the duration of a significant downturn. I know that is easier said than done when interest rates are as low as they are. Investors have a seemingly irresistible urge to ‘reach for yield’. But there is one thing that destroys wealth much more effectively than choosing the wrong fund here or there; investors that blindly carry risk almost always sell out at the first sign of trouble (effectively they ‘buy high and sell low’).

Steve Williams

You can read more articles about Pensions, Wealth Management, Retirement, Investments, Financial Planning and Estate Planning on my blog which gets updated every week. If you would like to talk to me about your personal wealth planning and how we can make you stay wealthier for longer then please get in touch by calling 08000 736 273 or email info@solomonsifa.co.uk