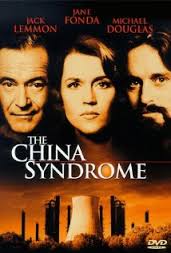

The China Syndrome

The recent severe volatility in China’s share markets has raised questions among many investors about the causes of the fall and about the wider implications for the global economy and markets generally.

The Shanghai Composite index, the mainland stock market barometer and one dominated overwhelmingly by retail investors, more than doubled in the year from mid-2014, only to lose more than 30% of its value in a month.

The volatility was much less in Hong Kong, where foreign investors tend to get their exposure to China. The Hang Seng index fell about 17% from April’s seven-year high, though it had a more modest run-up in the prior year of about 25%.

Nevertheless, the speed and scale of the fall on the Chinese mainland markets unsettled global markets, fuelling selling in equities, industrial commodities, and allied currencies like the Australian dollar and buoying perceived safe havens such as US Treasuries and the Japanese yen.

The decline in Chinese stocks triggered repeated interventions by China’s government, which has been seeking to transition the economy from a long-lasting export-led boom toward more sustainable growth based on domestic demand.

Investors naturally are concerned about what the volatility in the Chinese market means for their own investments and what it might signify for the global economy, particularly given the rapid growth of China in the past 20 years.

SHARE MARKET VS ECONOMY

Measured in terms of purchasing power parity (which takes into account the relative cost of local goods), the Chinese economy is now the biggest in the world, ranking ahead of the USA, India, Japan, Germany and Russia.1

Yet, China’s share market is still relatively small in global terms. It makes up just 2.6% of the MSCI All Country World Index, which takes into account the proportion of a company’s shares that are available to be traded by the public.

The Chinese market is also not a large part of the local economy. According to Bloomberg, it is capitalised at less than 60% of the country’s GDP. By comparison, the US equity market represents more than 100% of the US economy.

China is classified by some index providers as an emerging market. These are markets that fall short of the definition of developed markets on a number of measures such as economic development, size, liquidity and property rights.

China’s stock market is still relatively young. The two major national exchanges, in Shanghai and the other in the southern city of Shenzhen, were established only in 1990 and have grown rapidly since then as China has industrialised.

With foreign participation in mainland Chinese markets still heavily restricted, many foreign investors have sought exposure to China through Hong Kong or through China shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

As a consequence, domestic investors account for about 90% of the activity on the Chinese mainland market. And even then, the participation is relatively narrow. According to a China household finance survey, only 37 million or 8.8% of Chinese families held shares as of June 2015.2 As a comparison, just over half of all Americans own stocks, according to Gallup. In Australia, the proportion is 36%.

While the Chinese stock market is about 30% off its June highs, it nevertheless is still about 80% higher than it was a year ago. As such, much of the pain of the recent falls will have been felt by people who have entered the market in the past year.

A final point of perspective is that while the Chinese economy has been slowing, it nevertheless is still expanding at around 7% per annum, which is more than twice the rate of most developed economies.

The IMF in April projected growth would slow to 6.8% this year and to 6.3% in 2016. Still, it expects structural reforms and lower oil and commodity prices to expand consumer-oriented activities, partly buffering the slowdown.3

While such forecasts are subject to change, markets have priced in the risk of a further slowdown to what was previously expected, as seen in the renewed fall in the prices of commodities like copper and iron ore, which recently hit six-year lows.

DRIVERS OF THE BOOM

The Chinese share market boom of the past year cannot be attributed to a single factor, but certainly two major influences have been the Chinese government’s promotion of share ownership and investors’ increased use of leverage.

The government has been seeking to achieve more sustainable, balanced and stable economic growth after nearly four decades of China notching up heady annual growth rates averaging 10% on the back of an official investment boom.

But the transition to a shareholding economy has created its own strains. The outstanding balance of margin loans on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets had grown to 4.4% of market capitalisation by early July, according to Bloomberg.4

Under a margin loan, investors borrow to invest in shares or other securities. While this can potentially increase their return, it also exposes them to the potential of bigger losses in the event of a market downturn.

When prices fall below a level set by the lender as part of the original agreement, the investor is called to deposit more money or to sell stock to repay the loan. These margin call liquidations can amplify falling markets.

Chinese regulators, mindful of the potential fallout from the stock market drop, have instituted a number of measures to curb the losses and cushion the impact on the real economy.

These have included a reduction in official interest rates, a suspension of initial public offerings and enlisting brokerages to buy stocks backed by cash from the central bank. In the latest move, regulators banned holders of more than 5% of a company’s stock from selling for six months.

The government also has begun an investigation into short selling, which involves selling borrowed stock to take advantage of falling prices. In the meantime, about half of the companies listed on the two major mainland exchanges were granted applications for their shares to be suspended.

While such interventionist measures may seem alien to people in developed market economies, they need to be seen in the context of China’s status as an emerging market where governments typically play a more active role in the economy.

Whether the intervention works in the long term remains to be seen. But the important point is that this is a relatively immature market dominated by domestic investors and prone to official intervention.

SUMMARY

The re-emergence of China as a major force in the global economy has been one of the most significant drivers of markets in the past decade and a half.

China’s rapid industrialisation as the population urbanised drove strong demand for commodities and other materials. Investment and property boomed as credit expanded and as people took advantage of gradual liberalisation.

Now, China is entering a new phase of modernisation. The government and regulators are seeking to rebalance growth and bring to maturity the country’s still relatively undeveloped capital markets.

Nevertheless, China remains an emerging market with all the additional risks that this status entails. Navigating these markets can be complex. There can be particular challenges around regulation and restrictions on foreign investment.

We have seen those risks appearing in recent weeks as about a third of the sharp rise in the Chinese mainland market over the previous year was unwound in a matter of weeks, prompting intense government intervention.

Markets globally are weighing the wider implications, if any, of this correction. We have seen concurrent weakness in other equity markets and falls in commodity prices and related currencies.

Yet it is important to understand that the stock market is not the economy. China’s market is only about 2.6% of global market cap and its volatile mainland exchanges are for the most part out of bounds for foreign investors anyway.

For individual investors, the best course in this climate, as always, is to maintain diversification and discipline and to remember that markets accommodate new information instantaneously.

1. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2015

2. ‘China Households Raise Housing Investment in Q2’, Reuters, July 9, 2015

3. ‘World Economic Outlook’, International Monetary Fund, April, 2015

4. ‘China’s Stock Plunge Leaves Market More Leveraged than Ever’, Bloomberg, July 6, 2015

Jim Parker

Vice President, Dimensional

You can read more articles about Pensions, Wealth Management, Retirement, Investments, Financial Planning and Estate Planning on my blog which gets updated every week. If you would like to talk to me about your personal wealth planning and how we can make you stay wealthier for longer then please get in touch by calling 08000 736 273 or email info@solomonsifa.co.uk